Benzodiazepines and Your Patients:

A Management Programmeby

Roche Products (UK) Ltd

ca. 1990THE PRESCRIBING OF & WITHDRAWAL

FROM BENZODIAZEPINES[Note: This document was issued by Roche to prescribing physicians in the UK upon request.

Views, equivalencies, tapering and withdrawal advice given in this document are not necessarily

endorsed by the owner of this site and it is reproduced here for information purposes only.]When should you prescribe benzodiazepines?

There is no doubt that benzodiazepines have been of considerable benefit in the treatment of anxiety, insomnia, muscle spasm and epilepsy. However, there is increasing concern, both among doctors and the lay public regarding the potential for dependence on this group of drugs.

Benzodiazepines are the most commonly used anxiolytics and hypnotics. The prescriber must fully appreciate the differences in these indications since most anxiolytics will induce sleep when given in large doses at night and most hypnotics will sedate when given in divided doses during the day.

INSOMNIA

The cause of the insomnia should be established and where possible the underlying factors should be treated. Insomnia can be divided into different types as outlined in the British National Formulary.

Transient Insomnia

Transient insomnia may be due to a change in working pattern, jet lag, a noisy environment or some other extraneous and transient factor which will disappear in time. In these circumstances it may be desirable to prescribe for a few doses only, although assurance to the patient may be all that is required.

Short Term Insomnia

Short term insomnia is usually related to an emotional problem but sometimes to a serious medical condition.

Chronic Insomnia

Common causes of chronic insomnia will include psychiatric disorders such as anxiety, depression and drug and alcohol abuse. Other causes will include painful conditions such as arthritis and Parkinson's disease, pruritis, dyspnoea and nocturia.

Clearly it is desirable to establish the cause of the insomnia and treat this which, in many cases, will render the prescription of a hypnotic unnecessary. Indeed chronic insomnia can be worsened by the injudicious prescription of hypnotics.

Before resorting to the prescription of hypnotics it is also important to pay attention to the sleeping environment of the patients.

Many factors can affect a night's sleep and attention should be given to this (1):

Rise at a regular time in the morning, even after bad nights. This may strengthen the circadian rhythmicity of sleep and wakefulness, and lead to a more regular time of sleep onset.

Sleep adequately but not excessively. Excessively long times in bed may lead to fragmented and shallow sleep.

Take regular exercise during the day. Regular exercise encourages sound sleep, but occasional bouts of exercise do not.

Keep a comfortably cool room. A hot room disturbs sleep, though a cold room does not help to deepen sleep.

Do not go to bed hungry. A light bedtime snack, e.g. a warm milk drink, helps many people to sleep soundly.

Ensure a quiet bedroom. Occasional loud noises disturb sleep even if the subject has no recollection of waking. Soundproofed windows may be helpful.

Avoid caffeine. Coffee and tea lighten sleep, even in people who claim to be unaffected.

Avoid too much alcohol. Alcohol helps people fall asleep but the ensuing sleep is fragmented.

Do not try too hard. If sleep does not come easily get up and do something for an hour.

Use sleeping pills only exceptionally. The occasional use of hypnotics is justified to overcome an acute problem, but continued use should be avoided.

There are many different hygiene factors which may help an individual sleep without the necessity of hypnotics. When a benzodiazepine is necessary the Royal College of Psychiatrists (2) and the C.S.M. have issued advice on their use. The recommendations of the Royal College of Psychiatrists are outlined here:

Insomnia

disabling,

severe, or

subjecting the individual to extreme distress.

Benzodiazepines for sleep induction should ideally be given only intermittently either in in-patient or out-patient settings. As much care must be taken in the prescribing of benzodiazepines for insomnia as for anxiety.

There has been in the past an automatic assumption that benzodiazepines should be given for sleep disturbance. It is extremely important that doctors should look at the underlying causes for insomnia before deciding upon the use of drugs for symptomatic relief. If benzodiazepines are prescribed for insomnia, then this should be at a low dosage, not every night, and normally for a maximum period of one month.

ANXIETY

Anxiety is the final common pathway for different intrapsychic and biochemical processes. It is essential to remember this for benzodiazepines will affect the final common pathway and thus in the immediate short term help many anxious patients, but have no effect on the cause of their anxiety. Indeed benzodiazepines may mask important signs and symptoms and ultimately make treatment more difficult.

In the past there has been a tendency to prescribe benzodiazepines to patients with stress related symptoms, unhappiness and minor physical disease. (3) Their use in many of these circumstances is not justified. Even in more severe cases requiring drug therapy, diagnostic difficulties are encountered in the management of anxiety and these are most likely to occur when: (4)

|

the primary complaint is a physical symptom rather than anxious mood e.g. palpitation, change in bowel function. | |

|

the anxiety neurosis gives rise to a secondary condition e.g. depression secondary to anxiety, alcohol dependence secondary to anxiety. | |

|

the anxiety symptoms are the presenting feature of an organic illness e.g. thyrotoxicosis, phaechromocytoma, temporal lobe epilepsy. |

When a clear diagnosis has been made, the treatment of anxiety is similar to that of insomnia and involves many non-drug options such as:

-

Listening and talking.

-

Simple psychotherapy

-

Relaxation training.

-

Behaviour and cognitive therapy

When benzodiazepines are to be used in the treatment of anxiety the recommendations of the Royal College of Psychiatrists (2) and the C.S.M. are outlined here:

Benzodiazepines should be primarily prescribed for the short-term relief of anxiety when it is:

Anxiety

-

disabling,

-

severe, or

-

subjecting the individual to extreme distress.

In the above cases, benzodiazepines ideally should be prescribed for no more than one month.

Benzodiazepines may be prescribed where anxiety is complicated by other illnesses, but caution should be used in prescribing them when the disorder is already chronic. The long-term use of any compound to deal with mild anxiety is not in general advised. The consequences of long-term usage are liable to far outweigh the symptomatic relief.

There is not sufficient evidence to support the use of benzodiazepines for obsessional states.

When prescribing for either insomnia or anxiety it is important to be familiar with the appropriate data sheet(s) for the benzodiazepine(s) of your choice. It is also important to stress the risk of therapy as well as the benefits and to stress the short-term nature of this drug treatment.

Recognising a benzodiazepine-dependent patient

When dependence develops during prolonged continuous use of benzodiazepines, it is usually possible for the GP to recognise its existence and distinguish it from inadequately treated chronic anxiety or insomnia. Some important points are:

Patient Characteristics

There are individual patient characteristics which may predispose certain patients to become dependent on benzodiazepines, such as history of inappropriate use of alcohol or other drugs of dependence. Rarely, a drug-seeking behaviour is seen.

Timing of return of symptoms on stopping benzodiazepines

Symptoms of anxiety or panic may occur within about one to three days, depending on the elimination half-life of the benzodiazepine and its accumulative metabolites, and normally peak in intensity at about five to seven days. This time sequence helps distinguish dependence from the return of an inadequately treated chronic anxiety (Figure 1).

Figure 1. A Comparison of the pattern of symptoms

with dependence (—) and return of anxiety (---). (5)

Should every 'dependent' patient be withdrawn?

There are categories of patients in whom withdrawal is inadvisable. The first group is those in whom withdrawal should not even be attempted, for instance, patients with a chronic physical disorder controlled by the benzodiazepine (epilepsy or spastic muscular disorders). In addition, there are some patients, particularly the elderly, where the problems caused by withdrawal outweigh the risks of continued long-term, low-dose treatment.

The second group consists of patients in whom attempts should be made at withdrawal, but whose quality of life is so improved during the use of benzodiazepines that long-term therapy (preferably intermittent fluctuating dosage) is justified medically.

This group includes people with severe chronic anxiety and insomnia and an inadequate personality who find it difficult to exist in society if not supported by therapy. It also includes the dependent personality who relapses to alcohol or other more dangerous drugs if therapy is withdrawn. In such cases it would be wise to conduct a case review of the patient with a colleague before continuing treatment.

Since the nature and extent of the disability changes in the second group, further periodic withdrawal attempts are desirable.

Attempts at withdrawal are more likely to succeed if the doctor, the relatives, and particularly the patient want to achieve complete withdrawal. In this context the use of a "verbal contract" may be worthwhile. If a patient is either negative or indifferent in their attitude to withdrawal, then a successful outcome is less likely.

How should withdrawal be achieved?

In-patient facilities are scarce and the majority of uncomplicated benzodiazepine-dependent patients can be withdrawn by their own general practitioner, using simple dose reduction. Referral is, in most cases, unnecessary and the majority of patients will not need the more complicated methods of withdrawal which will be outlined later in this booklet.

However, there are several circumstances in which the general practitioner should be wary about attempting withdrawal and in which specialist advice and help should be sought (Table II).

| Previous severe withdrawal or postwithdrawal reaction Lack of adequate social support Elderly and infirm (if withdrawal must be undertaken) History of seizures History of inappropriate use of alcohol or other drugs of dependence Concomitant severe medical, biological or psychiatric problems Concomitant severe personality problems |

Table II. The main indications for seeking advice and help for

the withdrawal of benzodiazepines. (5)

Difficulty over withdrawal and the intensity of the withdrawal reactions vary from one benzodiazepine to the other. In general, the longer a patient has taken a particular benzodiazepine, and the larger the dose, the greater the withdrawal problem may be.

It should be remembered that abrupt withdrawal should be avoided, and that a successful outcome and maintained abstinence is unlikely without adequate emotional support from the general practitioner, the family, and friends.

Methods for benzodiazepine withdrawal

Any benzodiazepine withdrawal programme should be carefully planned and structured, the aim being to gradually reduce to zero the amount of drug being taken.

There is no single best technique for withdrawal, but simple dose reduction is best for most patients. Equally there are no specific data relating to the rate of withdrawal or the total time involved. Nevertheless, whichever technique is used, the regimen must be discussed with the patient, and the goals must be simple and attainable.

Withdrawal can be achieved by many methods. Each involves regular supervision by the general practitioner. For example, the general practitioner can simply gradually reduce the daily dose of the patient's current benzodiazepine over a period of several weeks; or the general practitioner can switch the patient's short-acting benzodiazepine for a long-acting one before attempting withdrawal; alternatively, the withdrawal programme can be supplemented with concomitant therapy.

Listed below are four methods which follow the general structure discussed above· They should be regarded purely as guidelines; the exact withdrawal programme should be tailored to the individual's response due to the wide variation in subjective response.

Method 1

Gradual reduction in dosage

This is the simplest and most common method for withdrawing a benzodiazepine. For example, it is recommended that temazepam be gradually withdrawn taking 10mg for 2 weeks, 5mg for 2 weeks and then 2.5mg for 2 weeks. Some authorities feel, however, the method is more appropriate for long acting benzodiazepines, and for shorter acting compounds they would recommend method 2.

Method 2

Substitution (7)

Substitute the short-acting benzodiazepine with an approximately equivalent dose of a long-acting drug such as diazepam (see the dose equivalent below). Because of diazepam's long elimination half-life, the withdrawal symptoms appear to be less severe with little associated 'craving'. However, there may be a problem with daytime sedation (8) if the short-acting benzodiazepine was for night sedation.

Substitution should be gradual and the benzodiazepine replaced in increments of one dose per day. This can usually be accomplished within one week but should be tailored to the individual patient. Some patients require a higher dose than the approximate equivalent.

Once substitution is achieved, a gradual reduction of the diazepam dosage should follow. Diazepam is available in 2mg, 5mg and 10mg tablets, all of which can be halved, and in an elixir 2mg in 5ml, which can be diluted.

Stepwise reductions in dosage should be made every week or fortnight, or even monthly, depending upon the patient's response.

Suggested reductions are:

Reduce by 2mg if daily dose 15mg to 20mg

Reduce by 1mg if daily dose 10mg to 15mg

Reduce by 0.5mg if daily dose 5mg

Tailor the dose reduction to patient response, ie weekly, fortnightly or monthly. Once patient is at a dosage of 0.5mg daily the dose interval can be increased to every two to three days.

Example

Replace the drug being used by equivalent doses of diazepam at the rate of one dose per day.

| Day | Morning | Afternoon | Evening |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Lorazepam | Lorazepam | Lorazepam |

| 2 | Lorazepam | Lorazepam | Diazepam 10mg |

| 3 | Lorazepam | Diazepam 10mg | Diazepam 10mg |

| 4 | Lorazepam | Diazepam 10mg | Diazepam 10mg |

| 5 | Diazepam 10mg | Diazepam 10mg | Diazepam 10mg |

| 6 | Diazepam 10mg | Diazepam 10mg | Diazepam 10mg |

A few patients have difficulties in changeover and may need to achieve this over a longer period of time.

Method 3 (9)

Dose reduction then immediate substitution to long-acting benzodiazepine followed by reduction

This approach combines Methods 1 and 2 and will make use of the greater flexibility in dosing of the longer acting preparations such as diazepam.

| BENZODIAZEPINE | REDUCE TO LOWEST DOSE | CHANGE TO LONG-ACTING BENZODIAZEPINE | PRESCRIBE SINGLE DAILY DOSE | FURTHER REDUCTION FOR 4 WEEKS | REASSESS 4 weeks minimum |

Whichever method is chosen, if the patient experiences troublesome abstinence effects after a reduction of dosage, the dose should be held at that level for a longer period before continuing the reduction at a slower rate. Try to avoid, if possible, increasing the dose at any stage.

Method 4

Adjuvant pharmacotherapy

Pharmacotherapy does not help with the psychological problems associated with benzodiazepine withdrawal, although it may help to reduce tension and anxiety with low doses of a sedative type antipsychotic drug.

However, it is possible to reduce some of the physical symptoms of withdrawal. Table III shows the pharmacotherapy which is accepted by many general practitioners as valuable.

| Manifestation | Proposed drug or drug group |

|---|---|

| Sympathetic overactivity e.g. tremor, sweating |

Propranolol for up to 3 weeks |

| Insomnia | A short course (about two weeks) of an effective hypnotic e.g. antihistamines, sedative antidepressants, the dose of which is gradually reduced |

| To avoid the risk of convulsions | Carbamazepine, or other anticonvulsants for up to 2 weeks may be necessary in rare cases |

Table III. Adjuvant pharmacotherapy which helps to reduce the

physical

symptoms of benzodiazepine withdrawal (5)

Long-term management of the successfully withdrawn patient

Although a significant proportion of patients who are dependent suffer no sequelae after the period of actual withdrawal (up to about eight weeks), some patients may experience a greater or lesser degree of discomfort for several weeks or months.

The actual symptoms experienced vary from one person to another, but the 'postwithdrawal syndrome' can manifest itself as fluctuating levels of malaise, lack of concentration, abdominal discomfort, depersonalisation, and emotional liability.

The most important single feature in the management of any stage of withdrawal is to encourage the patient to come to terms with their problems. Various forms of help available include support from the general practitioner, family and friends, self-help groups, relaxation methods, and counselling to remove the primary cause of the stress.

The period during which a relapse is most likely to occur is the first year after withdrawal. At the end of the first year, if adequate support has been given, there is a reasonable expectation that about 50% of those who could be withdrawn successfully would have remained benzodiazepine free. A proportion of the remainder will be using benzodiazepines only intermittently and sensibly.

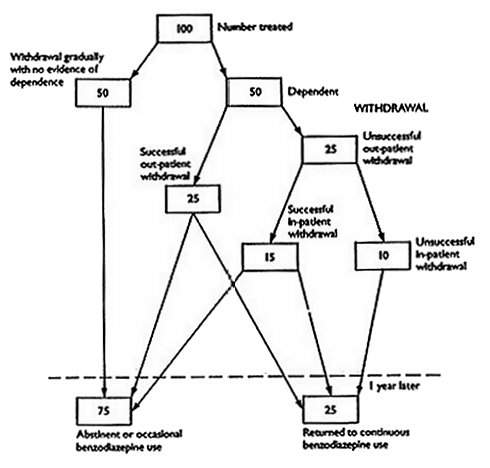

The results of withdrawal in an out-patient setting of low dose therapeutic benzodiazepine therapy are represented in Figure 2. Out of every 100 patients, 50 will be totally successful. Of the remaining 50, a further 25 will be successfully treated at a later date, and the other 25 will continue to take benzodiazepines to a varying degree.

Figure 2 - An approximate indication of the short- and long-term results of withdrawal

among those who have used benzodiazepines continuously for over one year.

On rare occasions it may be necessary to consider the prescription of a benzodiazepine to a patient who was dependent upon them previously. This should only be undertaken after all other avenues of treatment have been exhausted and in conjunction with an expert psychiatric opinion.

Specific Symptoms

Table I shows some of the signs and symptoms of benzodiazepine withdrawal. Some are related to anxiety and may make diagnosis more difficult but many are not and a careful enquiry needs to be made. Particularly related to withdrawal are the perceptual changes - most notably increased sensory perceptions such as hyperacusis, photophobia, paraesthesiae, hyperosmia and hypersensitivity to touch and pain. (6)

PRIMARY

Psychological

|

Tension | |

|

Agitation | |

|

Irritability | |

|

Panic sensations & panic attacks |

Physical

|

Dry mouth | |

|

Tremor | |

|

Sweating | |

|

Sleep disturbance | |

|

Lack of energy | |

|

Nausea |

Mental

|

Impaired memory and concentration |

SECONDARY

Moderate

|

Perceptual changes, e.g. Hypersensitivity to touch, light, sound, strange smells and tastes | |

|

Dysphoria - flu-like symptoms, lack of appetite, headaches, sore eyes | |

|

Depersonalisation | |

|

Depression |

Severe (rare)

|

Convulsions | |

|

Psychoses e.g. visual hallucinations, persecutory delusions |

Table I. The symptoms and signs of

benzodiazepine withdrawal

in the benzodiazepine dependent patient. (5)

Conclusion

In summary the vital aspects of withdrawal are:

-

Support from the doctor, family and friends.

-

In certain circumstances, the continued use of benzodiazepines is justified, even if dependence is present.

-

Gradual withdrawal in the doctor's surgery is the preferred method in uncomplicated cases and is successful for the majority of patients. If a short-acting benzodiazepine is being given, it may be substituted for a long-acting one. This is followed by gradual dose reduction over several weeks with adjuvant therapy.

-

There are several situations which indicate the need for specialist advice. (see above)

-

If depression is suspected, a sedative antidepressant should be considered. The benzodiazepine is continued. Gradual reduction of either drug can be accomplished once depression is successfully treated.

-

Postwithdrawal problems may occur. Good support from the general practitioner over at least the first year after withdrawal reduces the risk of relapse.

-

For multidrug high dose cases (usually sociorecreational use) withdrawal in a special hospital drug dependence unit should be considered.

References

-

Insomnia. A Guide for Medical Practitioners, Nicholson and Marks, MTP Press Ltd, 1983.

-

Priest, R., Montgomery, S. Bulletin of The Royal College of Psychiatrists, 1988, 12, 107·109.

-

Gelder, M. Medicine International 45: Sept 1987. Diagnosis and management of anxiety and phobic state.

-

Marks, J. Medical Toxicology 1988, 3, 324-333.

-

Higgit, A.C., Lader, M.H., Fonagy, P.B.M.T 1985, 291, 688-689.

-

Taylor, D. Br. J. Pharmaceut. Pract. 1988. 11 (3). 106-110.

-

Northern Regional Health Authority, Drug Newsletter, 1985, April, No 31.

-

Tyrer, P. MIMS Magazine, 1981, 1 July, 14-16.

![]()

BENZODIAZEPINES AND THEIR DIAZEPAM EQUIVALENTS

[But see also: Benzodiazepine Equivalence Table]

For the management of patients

who wish

to terminate benzodiazepine therapy

Doses of benzodiazepines approximately equivalent to 10mg diazepam. (It should be noted that widely varying half-lives make precise equivalents impossible to establish.)

| Current therapy | 10mg diazepam equivalent |

Reference |

|---|---|---|

| Alprazolam | 0.5mg 1mg |

2 3,4 |

| Bromazepam | 5mg 6mg |

5 2,4 |

| Clobazam | 20mg | 4 |

| Clonazepam | 4mg | 3 |

| Clorazepate | 7.5mg 15mg |

2 3,4 |

| Chlordiazepoxide | 20mg 25mg 50mg |

6 3,4 2 |

| Flunitrazepam | 1mg | 4 |

| Flurazepam | 15mg 30mg 15-30mg |

3 2 4 |

| Halazepam | 40mg | 3 |

| Ketazolam | 15-30mg | 4 |

| Loprazolam | 1-2mg | 4 |

| Lorazepam | 1mg 2mg |

4,7 2,3,6 |

| Lormetazepam | 1-2mg | 4 |

| Medazepam | 10mg | 4 |

| Nitrazepam | 5mg 10mg 20mg |

2 4 6 |

| Oxazepam | 10mg 20mg 30mg 60mg |

3 4 6 2 |

| Prazepam | 10mg 10-20mg |

3 4 |

| Temazepam | 15mg 20mg |

3 4,6 |

| Triazolam | 0.5mg 1mg |

4,6 2 |

Method 2 involves switching patients from short-acting to long-acting benzodiazepines as part of the withdrawal programme. The more gradual reduction in blood levels achieved with long-acting agents (for instance, diazepam) may result in less pronounced withdrawal symptoms.

Also, the fluctuations in blood levels between doses is less marked, and a single daily dose towards the end of the taper may give good 24-hour coverage. (1)

The conversion chart above gives you a quick and easy reference to the comparative strengths of commonly prescribed benzodiazepines, expressed in diazepam equivalents.

The values will help you assess the initial dosage of a drug such as diazepam that you should give your patient. Using the calculated dosage, you can replace the agent in their current treatment programme and aid their subsequent withdrawal.

References

Noyes, R et al. J. Clin. Psychiatry, 1988,49,382-389

Busto, U. et al. New Engl, J. Med., 1986,315, 854-859.

Perry, P.J. and Alexander, B. Drug Intell, Clin. Pharm., 1986,20,532

Taylor, D. Br. J. Parmaceut. Prac., 1989,11,106.

J. Roy. Coll. Gen. Pract., 1984,34,509.

Higgitt, A.C. et al. Br. Med. J., 1985,291,688.

Benzodiazepines: How they Work & How to Withdraw

by Professor C Heather Ashton, DM, FRCP, 2002

text from www.benzo.org.uk »

![]()